|

Anamnesis:

|

The patient,

K. H. Saraj,

a young man 30 years old, came to Jordan

from YAR 05-December-2009 complaining of fever

for one month duration with lethargy.

17-November-2009, when he was trying to travel

to Jordan, his condition deteriorated

dramatically and went to coma for what the

travel was post bonded. CT-scan and MRI

performed to him and several investigations were

performed. Lab investigations done for him:

HBc-Ab(IgG) positive 0.004 with toxoplasma

IgG (Automated ELISA) positive 918 IU/ml. These

data achieved 18-November-2009. WBC was 21.2

K/uL with neutrophils 92.4% (done

19-November-2009). WBC was 19.3 X10*9/L with

neutrophils 80% 20-november-2009. Toxo IgG

(Axsym) positive 26.9 IU/ml in 22-November-2009.

Toxo IgG (Axsym) positive 26.7 IU/ml in

24-November-2009. WBC 7.46 K/uL with

neutrophils 79.7%, GGT 38 IU/L recorded

26-November-2009. K+ was 2.8

mmol/L in 29-November-2009. K+

corrected to 3.4 mmol/L in 01-December-2009.

SGPT (ALT) was 66 IU/L and SGOT(AST) 40 IU/L in

02-December-2009. The patient was put in

mannitol and dexametasone pyrimethamine and

clindamycin. He was also covered with

antibiotics and aniviral and anti-tbc drugs. The

report provided with the patient confirming that

the patient was at admission comatose with

dilated both pupils and bradycardia

30/min. The patient slowly regained

consciousness and started to recover and was

oriented with normal vital signs before the

transfer. |

|

The

patient was seen in the ward at Shmaisani

hospital. He had severe headache and inability

to walk with still signs of lethargy and

projectile vomiting with Foleys catheter. He was

responding to verbal commands and moving four

limbs with good power. There was no sensory

deficit with slight meningism. There was massive

rash all over the body and yellow skin and eyes.

|

|

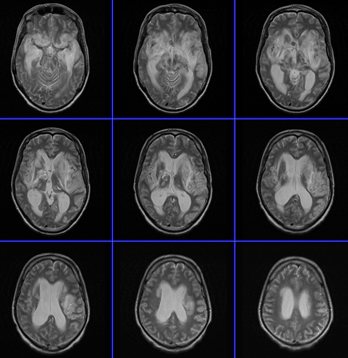

MRI of the brain was done

07-December-2009 and MRA of the brain with MRI

of the brain with contrast repeated

08-December-2009 showing the subependymar mass

in the region between the head of the right

caudate nucleus and the anterior commissure.

There was no aneurysm and there was still

enhancement of the ring around the mass, which

slightly shrunken in comparison to the MRI

performed 17-Novemeber-2009. |

|

Lab investigations were

performed and HIV-1 & 2 antibody were negative.

Toxoplasma IgG was 17.5 IU/ml, SGOT 97.0 U/L,

SGPT 209.0 U/L LDH 545.0 U/L GGT 67.0 U/L Folate

serum level 10.0 NG/ml done 08-December-2009. |

|

The patient was treated for

toxoplasmic encephalitis with abscess and the

patient projectile vomiting stopped and he could

walk the third post-admission day and the Foleys

catheter was removed 10-December-2009. He

admitted that the blurred vision disappeared. Chest and

abdomino-pelvic CT-scan done 11-December-2009

was normal. |

|

Gradual tapering of dexametasone started

10-December-2009. Mannitol was stopped 11-December-2009.

CD4-Lymphocyte count 465 cell/uL and SPECT was performed by

Tl-201 13-December-2009 confirming no evidence of active

lesion in the brain and the patient was discharged

14-December-2009. |

|

The patient,

then rapidly deteriorated in Yemen and

was admitted to the local hospital with severe

impairment of the level of consciousness with

right sided panophthalmoplegia and

aggressive treatment with mannitol, vancomycin,

antifungal and acyclovir was started. |

|

MRI performed there was not informative

and the MRA was looking with beaded arteries. ANCA was

positive. By telephone communication it was suggested that

the patient has vasculitis. The patient was sent back to

Jordan and was admitted to the ICU of Shmaisani hospital.

The patient is no locked in syndrome with right sided plegia

and some times yawning. He had nuchal rigidity with high

fever. |

|

The respiratory drive was compromised but

he was not in need for ventilation. MRI with contrast with

MRA and MRV done ruled out the presence of beaded arteries

and the presence of massive meningoencephalitis of the deep

basal ganglia both sides with involvement of the tentorium

and subtentorial structures. There was considerable

dilatation of the ventricular system. ANCA was repeated

twice and it was negative. The patient was started with the

same treatment as In Yemen and external drain was inserted

to the right lateral ventricle. The CSF was yellowish and

sent for all possible investigations. Only yeast could be

found in one specimen and was not found in others. The

pressure of the CSF was almost normal and mannitol was

stopped. All virology studies were normal and blood

for CXS was negative. Duflucan was increase and the

toxoplasmosis drugs were all the time kept. Meropnem

was started 1 gm QTD. |

|

HIV tests were repeated and they were

negative. The patient was given petaglobin over three days

without any signs of improvement. |

|

The external drain was removed after 7

days and 2 days later tapering the dexametasone was

started. The patient after slight improvement during the

first week started to show gradual deterioration 3 days

after tapering dexametasone, for what it was put back in

track. |

|

The patient progressed signs of

decerebration with flexor spasms, for what senimet was given

and the next day Liorezal 5 mg was added. The patients

rigidity disappeared and the respiratory drive got worse,

for what Liorezal was stopped. |

|

Two days later after stopping Liorezal

the patient showed slight improvement in the motor functions

and the rigidity disappeared, which means that he got severe

sensitivity to Liorezal. |

|

MRI of the brain with contrast was

repeated 11-February-2010 which showed dramatic

deterioration of the lesion with involvement of the temporal

lobes more to the left and the pons. CSF was obtained

through the old ventricular catheter site and sent for

routine and antitbc PCR. The old investigated CSF for fungi

needs 45 days to identify the type of fungi, which could be

negative. |

|

|

|

MRI performed 11-February-2010 showed

further deterioration despite aggressive treatment. |

|

The patient in 12-February-2010 showing

slight improvement, and due to financial problems the

patient relatives decided to transfer him back to Yemen. |

|

The patient has very aggressive

meningo-encephalitis of protracted and relapsing and

remitting character. Covering all the causative possible

cause, the morphologic changes got worse and worse. Could

toxoplasmosis can lead to such events, still a dilemma.

|

Toxoplasmosis

in HIV-infected patients

INTRODUCTION — Toxoplasmosis, an

infection with a worldwide distribution, is caused by the

intracellular protozoan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii. Immunocompetent

persons with primary infection are usually asymptomatic, but latent

infection can persist for the life of the host.

In immunosuppressed patients, especially patients with the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the parasite can reactivate and

cause disease, usually when the CD4 lymphocyte count falls below 100

cells/µL. All patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

infection should be screened for T. gondii antibodies. Counseling on

preventing toxoplasmosis should be given to those who are

seronegative and prophylaxis initiated, when appropriate, for

seropositive patients.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence of infection — Seroprevalence rates of toxoplasmosis vary

substantially among different countries (eg, approximately 15

percent in the United States to more than 50 percent in certain

European countries). Among HIV-infected patients, seroprevalence of

antibodies to T. gondii mirror rates of seropositivity in the

general population. Among 2525 women in the United States, for

example, the T. gondii seroprevalence was 15 percent and did not

differ based upon whether or not the individual had HIV. Those with

HIV were more likely to have antibodies to T. gondii if they were 50

years of age or born outside of the United States. In patients with

AIDS, there is no higher incidence of toxoplasmosis in cat owners

compared to non-cat owners.

Patients with AIDS and <100 CD4 cells/µL, who are toxoplasma

seropositive, have an approximately 30 percent probability of

developing reactivated toxoplasmosis if they are not receiving

effective prophylaxis. The most common site of reactivation is the

central nervous system (CNS); toxoplasmosis is the most common

parasitic CNS opportunistic infection (OI) in AIDS patients , except

in patients who are on appropriate prophylaxis.

|

Toxoplasmic encephalitis —

The incidence of toxoplasmic encephalitis in

AIDS patients reflects seropositivity rates in

this population; HIV-infected patients from

Florida, for example, had a higher

seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies and a

greater prevalence of toxoplasmic encephalitis

in one study. However, the introduction of

anti-toxoplasma prophylaxis and highly active

antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has altered the

occurrence of toxoplasmic encephalitis like

other OIs. In the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study

(MACS), the incidence of CNS toxoplasmosis

decreased from 5.4 per 1000 person-years in 1990

to 1992 to 3.8 per 1000 person-years in 1993 to

1995 and, 2.2 per 1000 person-years in 1996 to

1998 after HAART began to be widely used. |

|

Extracerebral toxoplasmosis — It is much

harder to determine the incidence of extracerebral

toxoplasmosis. Most of the available data are from before

the introduction of HAART and from France where the

seroprevalence to T. gondii is high. In one French series of

1,699 HIV-infected patients, for example, the overall

incidence of toxoplasmosis was 1.53 cases per 100

person-years for the years 1988 to 1995 (compared to 5.4 or

3.8 cases per 1000 person-years in the United States). The

distribution of extracerebral cases is illustrated by the

following: In the series of 1,699 patients, 116 cases of

confirmed, probable or possible toxoplasmosis was diagnosed;

cerebral toxoplasmosis accounted for 89 percent, with

pulmonary, ocular, and disseminated infection responsible

for 6, 3.5, and 1.7 percent of cases, respectively. Another

French series of 199 HIV-infected patients with

extracerebral toxoplasmosis evaluated between 1990 and 1992

estimated that the prevalence of extracerebral toxoplasmosis

among AIDS patients was 1.5 to 2 percent. Among these

selected patients, eye involvement occurred in 50 percent,

lungs in 26 percent, two or more extracerebral sites in 11.5

percent, and peripheral blood, heart, and bone marrow in 3

percent each. Involvement of the bladder, pharynx, skin,

liver, lymph nodes, conus medullaris, and pericardium also

were demonstrated in rare cases. Widespread distribution may

be more common pathologically than clinically appreciated.

This was suggested in an autopsy study in which the most

common extracerebral sites of toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected

patients were the heart, lungs, and pancreas with 91, 61,

and 26 percent of cases, respectively.

The most prominent risk factor for the development of

extracerebral toxoplasmosis is advanced immunosuppression

(mean CD4 counts of 57 and 58 cells/µL in two of the French

series). Concurrent CNS disease was present in 41 percent of

patients in the report of 199 extracerebral cases.

|

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

— As noted above, when T. gondii reactivates in a patient with AIDS,

it most commonly does so in the CNS leading to cerebral abscesses.

The clinical manifestations of toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent

patients are discussed separately.

|

Toxoplasmic encephalitis —

Patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis typically

present with headache. In one retrospective

review of 115 cases, 55, 52, and 47 percent had

headache, confusion, and fever, respectively.

Focal neurologic deficits or seizures are also

common. Fever is usually, but not reliably,

present. Dull affect may be due to global

encephalitis but more profound mental status

changes, especially accompanied by nausea or

vomiting, usually indicates elevated

intracranial pressure. |

Extracerebral toxoplasmosis

|

Pneumonitis — Pneumonitis, as

an extracerebral manifestation of toxoplasmosis,

presents with fever, dyspnea and non-productive

cough. Chest radiographs typically have

reticulonodular infiltrates. The clinical

picture may be indistinguishable from

Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly carinii)

pneumonia (PCP). Some have suggested that a

blood level of lactate dehydrogenase >600 U/L is

more likely to be associated with toxoplasmosis

than PCP. However, others have found that LDH is

elevated in both of these infections.

|

|

Chorioretinitis — Patients with

toxoplasmic chorioretinitis (a posterior uveitis) usually

present with eye pain and decreased visual acuity. These

symptoms and signs do not distinguish this entity from other

ocular infections in HIV, especially cytomegalovirus (CMV)

retinitis. Toxoplasmic chorioretinitis appears as raised

yellow-white, cottony lesions in a non-vascular

distribution, unlike the perivascular exudates of CMV

retinitis. Vitreal inflammation is usually present in

contrast to ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent

patients. Chorioretinitis due to T. gondii can rarely mimic

acute retinal necrosis. Up to 63 percent of AIDS patients

with toxoplasma chorioretinitis will have concurrent CNS

lesions. |

|

Other manifestations — Toxoplasmosis can

rarely present with involvement of a variety of other sites

in patients with AIDS including: gastrointestinal tract,

liver, musculoskeletal system, heart, bone marrow, bladder,

spinal cord, and orchitis. In the French series,

toxoplasmosis of the pancreas or muscular system did not

occur in the absence of involvement at other sites. Nine

patients with disseminated toxoplasmosis presenting with

septic shock were reported from France; in two patients this

appeared to be primary infection. |

DIAGNOSIS

— Toxoplasmosis frequently enters the differential diagnosis in an

AIDS patient with focal brain lesions. The vast majority of patients

with toxoplasma encephalitis are seropositive for anti-toxoplasma

IgG antibodies. Anti-toxoplasma IgM antibodies are usually absent

and quantitative IgG antibody titers are not helpful. The absence of

antibodies to toxoplasma makes the diagnosis less likely, but does

not exclude the possibility of TE.

To establish a definitive diagnosis in patients with extracerebral

toxoplasmosis, the demonstration of tachyzoites in tissue or fluid,

such as BAL, is usually required.

Cerebral toxoplasmosis — Most AIDS patients with cerebral

toxoplasmosis have multiple, ring-enhancing brain lesions often

associated with edema. In a report of 45 patients who underwent

computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 31 (69

percent) had multiple lesions and 14 had single lesions. There is a

predilection for involvement of the basal ganglia.

MRI versus CT — Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive

than computed tomography (CT) for identifying these lesions. In one

prospective study of 50 AIDS patients with neurologic symptoms, for

example, MRI detected abnormalities that influenced diagnosis and

treatment in 40 percent, which were not characterized by CT.

However, there is an extensive differential diagnosis for brain

lesions in AIDS patients and the appearance by either CT or MRI does

not adequately distinguish among these. Toxoplasmosis and CNS

lymphoma are the two most common entities (representing 50 and 30

percent, respectively), but other infections, including

cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, aspergillosis, tuberculosis and

trypanosomiasis may also cause brain abscesses in patients with

AIDS.

SPECT imaging — Thallium single photon emission computed

tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) can be

useful in distinguishing toxoplasmosis or other infections from CNS

lymphoma. Lymphoma has greater thallium uptake on SPECT and greater

glucose and methionine metabolism on PET than neurotoxoplasmosis or

other infections.

Brain biopsy — Definitive diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis is

made by pathologic examination of brain tissue obtained by open or

stereotactic brain biopsy. Organisms are demonstrated on hematoxylin

and eosin stains; some laboratories also use immunoperoxidase

staining which may increase diagnostic sensitivity.

However, there is morbidity and even mortality associated with the

procedure. In one series of 136 patients, morbidity and mortality of

brain biopsy was 12 and 2 percent, respectively. Morbidity rates

have been reported to be 3 to 4 percent. Due to these concerns, it

is common practice to presumptively diagnose and treat cerebral

toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients if the clinical suspicion is high. A

presumptive diagnosis can be made if the patient has a CD4 cell

count <100/µL and: Is seropositive for T. gondii IgG antibody Has

not been receiving effective prophylaxis for toxoplasma. Brain

imaging demonstrates a typical radiographic appearance (eg, multiple

ring-enhancing lesions)

If these three criteria are present, there is a 90 percent

probability that the diagnosis is toxoplasmosis, and thus, it is

common practice to treat empirically for toxoplasmosis. If a

solitary lesion is detected, even if toxoplasma serology is

positive, CNS lymphoma rises on the differential diagnosis list. If

all three of the above criteria are not met, biopsy or other

diagnostic tests should be performed. Brain biopsy should also be

performed if the patient does not respond to empiric therapy, on the

basis on clinical or radiographic improvement.

A group has questioned the reliability of the presumptive

diagnostic approach in favor of earlier biopsy. In one study, the

positive predictive value of the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) criteria for the diagnosis of toxoplasmic

encephalitis declined from 100 to 39 percent from 1991 to 1996. An

increase in use of prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis and increases

in other causes of CNS focal lesions were deemed largely responsible

for this difference.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for other pathogens (eg,

Epstein-Barr virus [EBV], JC virus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis,

Cryptococcus neoformans) can be considered in patients with focal

brain lesions who were already taking prophylactic antibiotics for

toxoplasmosis or were seronegative. The prevalence of these other

infections in HIV-infected patients and other clinical clues from

the presentation should influence which specific tests are ordered.

CSF analysis — Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may have mild mononuclear

pleocytosis and elevated protein. T. gondii can be detected in CSF

by DNA amplification in most patients with CNS infection.

Tachyzoites can sometimes be seen on cytocentrifuged cerebrospinal

fluid samples stained with Giemsa.

TREATMENT — A number of

therapies are available for the treatment of toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasmic encephalitis generally responds promptly to treatment.

Lack of either clinical or radiographic improvement within 10 to 14

days of empiric therapy for toxoplasmosis should raise the

possibility of an alternative diagnosis. Extracerebral toxoplasmosis

is treated with the same regimens as toxoplasmic encephalitis,

although the response may not be as favorable.

The following are treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH,

and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA):

First-line therapy — Two combination regimens are considered to be

first choices for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. All pyrimethamine

regimens should include folinic acid to prevent drug-induced

hematologic toxicity (10 to 25 mg/day PO).

Pyrimethamine (200 mg

loading dose PO followed by 75 mg/day) plus

sulfadiazine (6 to 8

g/day PO in four divided doses). For those patients who cannot take

sulfadiazine due to intolerance or history of allergy, pyrimethamine

(200 mg loading dose PO followed by 75 mg/day) plus clindamycin (600

to 1200 mg IV or 450 mg PO four times a day) is recommended.

Pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine has a higher incidence of cutaneous

hypersensitivity reactions compared with pyrimethamine plus

clindamycin but may have a lower incidence of relapse. Patients

receiving sulfadiazine therapy do not require additional TMP-SMX for

PCP prophylaxis. One study documented equivalent pharmacokinetic

parameters for 2000 mg of sulfadiazine administered twice daily

compared to 1000 mg given four times a day. Treatment for pregnant

females is the same as in nonpregnant females.

Alternative regimens — Several alternative regimens have been used,

generally in patients who are unable to tolerate either sulfadiazine

or clindamycin: Pyrimethamine (200 mg loading dose PO followed by 75

mg/day) plus azithromycin (1200 to 1500 mg PO once daily)

Pyrimethamine (200 mg loading dose PO followed by 75 mg/day) plus

atovaquone (750 mg PO four times a day) Sulfadiazine (1500 mg four

times a day) plus atovaquone (1500 mg twice daily)

If atovaquone is used, measuring plasma levels might be helpful

since there is significant individual variation in drug absorption

and higher plasma concentrations are associated with better

outcomes.

A pilot, multicenter, randomized prospective trial evaluated the

efficacy and safety of trimethoprim (TMP) and sulfamethoxazole (SMX)

compared to standard therapy with pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine.

Seventy-seven patients were randomly assigned to receive TMP (10

mg/kg/day) and SMX (50 mg/kg/day) as acute therapy for four weeks

followed by maintenance therapy for three months at half of the

original dosage. There was no statistically significant difference

in clinical efficacy between the two arms. Adverse effects were more

common in the patients treated with pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole may be an effective alternative

treatment regimen, particularly in resource-poor settings.

In critically ill patients, intravenous administration of TMP 10

mg/kg/d + SMX 50 mg/kg/d, can be considered, although is less

effective.

As above, pyrimethamine therapy should always be accompanied by the

administration of folinic acid (10 to 25 mg/day PO). Some of these

regimens, especially those using atovaquone, have been tried as

salvage therapy in patients failing to respond to a first-line

regimen. However, reconsideration of the diagnosis should be the

first response to a patient who appears to be failing therapy.

Duration of therapy — For patients who respond, the duration of

therapy is typically six weeks at the doses recommended above.

Following that treatment, it is usually safe to decrease to a lower

dose for secondary prophylaxis (chronic suppressive therapy).

Steroids — Adjunctive corticosteroids should be used for patients

with radiographic evidence of midline shift, signs of critically

elevated intracranial pressure or clinical deterioration within the

first 48 hours of therapy. Dexamethasone (4 mg every six hours) is

usually chosen and is generally tapered over several days.

When corticosteroids are used, it may be difficult to assess the

clinical response to antibiotics since the rapid improvement in

symptoms may be due to steroid therapy. Radiographic assessment is

also affected since the corticosteroids will reduce the intensity of

ring-enhancement and the amount of surrounding edema. If steroids

are used, patients should also be carefully monitored for the

development of other opportunistic infections.

Anticonvulsants — Anticonvulsants should be administered to patients

with a history of seizures, but should not be given routinely for

prophylaxis to all patients with the presumed diagnosis of TE.

Careful attention needs to be paid to any potential drug

interactions.

Monitoring of therapy — Monitoring of

patients includes careful clinical evaluations, serial brain

imaging, and assessment of any adverse effects of therapy. There is

no value to serial assessment of IgG toxoplasma antibody titers.

Common side effects of pyrimethamine include rash, nausea, and bone

marrow suppression. Higher doses of leucovorin up to 50 to 100 mg

daily can be considered for management of hematologic abnormalities.

Sulfadiazine use can lead to rash, fever, leukopenia, hepatitis,

nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and crystalluria. Clindamycin use can

also lead to fever, rash, nausea and diarrhea related to production

of Clostridium difficile toxin.

Response to therapy — Clinical

improvement usually precedes radiographic improvement. Thus, a

careful daily neurologic examination is more important than

radiographic studies in assessing the response to therapy during the

first two weeks of treatment. Radiographic reassessment should be

deferred for two to three weeks unless the patient has not

demonstrated clinical improvement within the first week or has shown

any worsening.

The literature on response to therapy is hampered by presumptive

diagnoses, cross-over treatments, and discontinuation for toxicity

rather than lack of clinical response. There are no randomized,

double-blind trials. The comparative trials on different treatment

regimens suggest that approximately 80 percent of patients

demonstrate clinical and radiologic responses.

One study focused on the timing of the response in 49 patients

treated with pyrimethamine plus clindamycin [22]. Seventy-one

percent responded overall with 32 of the 35 patients demonstrating

improvement of at least 50 percent of baseline abnormalities by day

14 of therapy. The authors concluded that early neurologic

deterioration or lack of neurologic improvement (except for headache

and seizures) by day 10 to 14 should raise the possibility of an

alternative diagnosis and such patients should be considered for

brain biopsy. (See "Approach to HIV-infected patients with central

nervous system lesions").

PROPHYLAXIS — Patients

seropositive for T. gondii should receive prophylaxis according to

the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC), United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the

Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

Primary prophylaxis — Prophylaxis is

indicated for patients with HIV and CD4 counts <100 cells/µL who are

T. gondii IgG positive. Patients who have negative toxoplasma

serology should be counseled to avoid eating undercooked meats and

to use gloves when carefully cleaning cat litter boxes. They do not

need to avoid contact with household cats entirely.

Secondary prophylaxis — As noted above

in the treatment section, following six weeks of therapy, patients

can receive lower doses of drugs which is considered secondary

prophylaxis or chronic suppressive therapy.

Sulfadiazine (2 to 4 g daily in 4 divided doses) plus pyrimethamine

(25 to 50 mg daily) is the first choice for secondary prophylaxis.

Folinic acid (10 mg to 25 mg daily) is also given concurrently.

Alternative regimens include: Clindamycin (300 mg PO QID or 450 mg

PO TID) plus pyrimethamine (25 to 50 mg daily) plus folinic acid (10

to 25 mg daily. Atovaquone 750 mg PO 2 to 4 times daily with or

without pyrimethamine 25 mg PO daily plus folinic acid 10 mg PO

daily.

Atovaquone monotherapy 750 mg four times daily can be considered for

patients who cannot tolerate pyrimethamine but the one year relapse

rate is 26 percent.

Toxoplasmosis prophylaxis and immune

reconstitution — If the CD4 count rises above 200

cells/µL for three months, primary prophylaxis for both PCP and

toxoplasmosis can be safely discontinued.

The issue of secondary prophylaxis is more complex. Patients appear

to be at low risk for recurrence of TE if they have completed

therapy, remain asymptomatic, and have a sustained increase in their

CD4+ T lymphocyte counts greater than 200 cells for more than six

months. The CDC/USPHS/IDSA guidelines state that if immune

reconstitution is maintained for six months, then secondary

prophylaxis for TE can be discontinued.

The clinician needs to remember that the number of patients who have

been evaluated with this approach is limited and the patient should

be educated about symptoms that should lead to a prompt medical

evaluation. Primary or secondary prophylaxis should be re-initiated

if the CD4+ T lymphocyte count declines to less than 200

cells/microL.

SUMMARY Seroprevalence

to T. gondii depends upon the part of the world in which the patient

was born and resided more than upon the patient's HIV status.

Toxoplasma encephalitis is the most common presentation of

toxoplasmosis as an OI among AIDS patients and occurs most commonly

in those with a CD4 count <100 cells/µL. Prophylaxis against PCP and

the widespread use of HAART in developed countries has greatly

decreased the incidence of this infection. The diagnosis of

toxoplasma encephalitis is usually made presumptively in an AIDS

patient with CD4 count <100/µL, a positive T. gondii IgG antibody,

no recent prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis, and multiple

ring-enhancing lesions on brain imaging. Brain biopsy can yield the

diagnosis in patients who don't meet the above criteria or whose

lesions fail to respond to presumptive therapy. First-line therapies

for cerebral toxoplasmosis include pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine

or pyrimethamine plus clindamycin. Alternatives include

pyrimethamine plus azithromycin, pyrimethamine plus atovaquone,

sulfadiazine plus atovaquone, or as a last resort TMP/SMX. Folinic

acid must always accompany pyrimethamine therapy. Corticosteroids

are often administered in conjunction with antibiotics in patients

with signs of significant increased intracranial pressure. The doses

of pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine or pyrimethamine/clindamycin are

usually lowered for maintenance treatment after approximately six

weeks of therapy. Primary prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis is

usually given to patients with CD4 counts <200 cell/µL. TMP-SMX in

the doses given for PCP prophylaxis is the usual choice to

accomplish prevention of both OIs. Both primary and secondary

prophylaxis (maintenance therapy) can be discontinued in patients

who achieve immune reconstitution with HAART.

Comments

|

The Toxo IgM (Axsym) was all

the time negative in this case. The patient had

no HIV. |

|

The causative cause of his

rapid deterioration was the escalation of rapid

increase in ICP, because the abscess was near

the foramen of Monroe. |

|