|

Anamnesis

|

The patient came to the clinic 25-February-2004

complaining of severe headache for several

months and blurred vision lat month with

anosmia. |

|

MRI brain with contrast done 14-February-2004

showing huge olfactory groove meningioma more to

the left with massive edema over the left

cerebral hemisphere. |

|

On examination: The patient has anosmia with

decreased visual functions more the left eye

with scatomas. She had episodes of vomiting the

last 2 weeks. The patient has epiattacks and she

felt down in the bathroom one week ago. |

|

Modified left bifrontal

craniotomy done with reflection of the bone flap

to the left ear. The brain is severely swollen

and all measures to decrease the swelling

failed. Trying to minimize the traction injury,

the tumor was approached and piece-meal

resection was achieved. Total resection of the

mass was done, but the brain swelling persisted.

The wound was closed, so that the dura was not

pushing the brain. The patient was extubated and

sent to the ICU. The patient still drowsy and

she was sent for control CT-scan of the brain,

which revealed very huge occipital hematoma. The

patient was taken to the operating room and the

hematoma was evacuated, after what good recovery

was achieved. |

FOLLOW UP

|

The patient had huge extradural hematoma, which

was the cause of the swelling and made the first

operation difficult. Usually after resection of

the tumor. the brain becoming lax and

regain good pulsation, but here was not the

case. |

|

In retrospective analysis, the hematoma must be

diagnosed first and removed and then remove the

tumor. But for several reasons the hematoma was

missed and the first surgery was very difficult. |

|

In the future do the MRI investigations

immediately before surgery. |

|

The patient came

to the clinic

09-April-2007 to discontinue Epanutin. She is convulsion free for

three years. On examination, the right eye still having decreased

vision with bilateral anosmia. |

OLFACTORY GROOVE MENINGIOMAS

Clinical Features

These tumors arise from the midline of the anterior

fossa between the crista Galli and the tuberculum

sella. They are usually bilateral but may be asymmetric

and attain a large size before causing symptoms. The

most common presenting symptom is a subtle change in

mental function or headache alone or in combination with

mental function change, but a disturbance in vision or a

seizure disorder may also be the initial manifestation.

Loss of the sense of smell was recorded as "possibly"

the primary symptom in only 3 of 28 patients in

Cushing's series, and he questioned the reliability of

this finding.

MRI clearly defines the extent of the tumor, the edema

in the surrounding brain, the relationship of the tumor

to the optic nerves and anterior cerebral arteries, and

any extension into the ethmoid sinus. Angiography is

rarely needed.

Surgical Management

In planning the operation, it is important to remember

that the blood supply comes into the tumor through the

bone in the midline of the anterior fossa from branches

of the ethmoidal, middle meningeal, and ophthalmic

arteries; the posterior capsules may be attached to the

optic nerves, chiasm, and anterior cerebral arteries.

For patients with a large tumor, It is preferable to

perform a bifrontal craniotomy. This approach is

associated with the least amount of retraction on the

frontal lobes, gives direct access to all sides of the

tumor, and allows the surgeon to decompress the tumor

while working along the base of the skull to interrupt

the blood supply. For smaller tumors, a right subfrontal

approach coming from laterally over the orbital roof, as

for tuberculum sella meningioma, may be used. Some uses

a pterional approach. Others use either exposure and may

resects part of the frontal lobe. The patient is placed

carefully in the supine position with the head elevated

and slightly extended. Using a coronal incision, the

skin flap and underlying tissue, including pericranial

tissue, are turned down together. Burr holes are placed

just below the end of the anterior temporal line and on

each side of the saggital sinus at the level of the skin

incision. The cut just above the supraorbital ridge is

made from each side as far medially as possible. Usually

this leaves a centimeter or less of bone in the midline.

Because of the irregular bone projecting from the inner

table of the skull in this area, it is often not

possible to cut completely across the area, but the

external table can be cut with a fine drill attachment

and the bone can be broken at this point. The frontal

sinuses are almost always entered. The mucosa is removed

and the sinuses are packed with bacitracin-soaked

Gelfoam. A flap of pericranial tissue from the back of

the skin flap is turned down over the sinuses and sewn

to the adjacent dura. The dural incision is made over

each medial inferior frontal lobe just above the edge of

the craniotomy opening. While the frontal lobes are

retracted carefully, the superior sagittal sinus is

divided between two silk sutures and the falx is cut.

The frontal lobes are then retracted carefully laterally

and slightly posteriorly. The tumor will come into view

in the midline; at times it is found to have grown into

the region of the crista galli and falx. The anterior

capsule of the tumor is exposed, and then an extensive

internal decompression is done. The base of the tumor in

the midline is gradually divided, interrupting the blood

supply that is coming in through numerous openings in

the bone. These are occluded with coagulation and bone

wax. The capsule can now be reflected into the area of

the decompression without undue pressure on the frontal

lobes. Great care is taken during the dissection of the

posterior portion of the capsule. The surgeon reflects

it anteriorly and is careful to look for the

pericallosal branch of each anterior cerebral artery.

The frontal polar branch will often be adherent to the

tumor and may need to be divided. It is usually possible

to follow the capsule back to the sphenoid wing and

then, working medially, to identify the anterior clinoid

processes and the optic nerves. At times it may be

difficult to see the nerves because of the posterior and

inferior compression and the thickened arachnoid.

However, under magnification, the tumor can be reflected

off the optic nerve(s). Once the bulk of the tumor is

removed, the dural attachment is totally excised and any

bone hyperostosis removed, with care taken to avoid

entering the ethmoid sinus unless it is known that the

tumor extends into the sinus. The region of the

cribriform plate is covered with a graft of pericranial

tissue and Gelfoam to prevent a cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) leak.

Results

Complete removal can be achieved in 90% of cases and 5%

with a radical subtotal removal with a small fragment

left on the internal carotid artery or other vitally

important structures. In 90% of patients a good result

can be achieved. Postoperative death due to various

causes is around 5%.

The incidence of complications is low and do not

interfere with eventual recovery. CSF leak through the

ethmoid sinus that required transethmoidal repair can be

in 5% of cases. A wound infection also 5%, A subdural

hygroma requiring a subdural-peritoneal shunt in 5%.

Disturbance in mental function and personality changes

when present preoperatively or transiently in the

postoperative period usually recover completely.

Preoperative visual symptoms usually recover and

headache is relieved.

Background

A systematic investigation of long-term follow-up

results after microsurgical treatment of patients

harbouring an olfactory groove meningioma, particularly

with regard to postoperative olfactory and mental

function, has rarely been performed. We reassessed a

series of patients treated microsurgically for an

olfactory groove meningioma in regard to clinical

presentation, surgical approaches and long-term

functional outcome. Method. Clinical, radiological and

surgical data in a consecutive series of 56 patients

suffering from olfactory groove meningioma were

retrospectively reviewed.

Findings. Presenting symptoms of the 41 women and 15 men

(mean age 51 years) were mental changes in 39.3%, visual

impairment in 16.1% and anosmia in 14.3% of the

patients. Preoperative neurological examination revealed

deficits in olfaction in 71.7%, mental disturbances in

55.4% and reduced vision in 21.4% of the cases. The

tumour was resected via a bifrontal craniotomy in 36, a

pterional route in 13, a unilateral frontal approach in

4 and via a supraorbital approach in 3 patients. Extent

of tumour resection according to Simpsons

classification system was grade I in 42.9% and grade II

in 57.1% of the cases. After a mean followup period of

5.6 years (range 113 years) by clinical examination and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 86.8% of the patients

resumed normal life activity. Olfaction was preserved in

24.4% of patients in whom pre- and postoperative data

were available. Mental and visual disturbances improved

in 88 and 83.3% of cases, respectively. Five recurrences

(8.9%) were observed and had to be reoperated.

Conclusions

Frontal approaches allowed better resection of tumours

with gross infiltration of the anterior cranial base,

tumours extending into the ethmoids or nasal cavity and

in cases with deep olfactory grooves. Preservation of

olfaction should be attempted in patients with normal or

reduced smelling preoperatively.

Introduction

Meningiomas of the midline anterior skull base include

tumours originating from the dura of the cribriform

plate, planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae and

account for about 10% of all intracranial meningiomas

[41]. For clinical, radiological and surgical purposes

true olfactory groove meningiomas, i.e. tumours

originating from the dura between the crista galli and

the frontosphenoid suture should be differentiated from

planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae meningiomas [8,

32]. Tumours arising from the latter sites usually come

to clinical attention at an early stage with visual

deterioration, while this is a late feature in olfactory

groove meningiomas which usually remain clinically

quiescent during the early phase of growth.

Anatomically, olfactory groove meningiomas arise from

the weakest part of the skull base, the cribriform

plate, which makes them prone to infiltrate the

underlying bone and extend into the paranasal sinuses

and nasal cavity. This is a rare feature in planum

sphenoidale or tuberculum sellae meningiomas.

A systematic assessment of functional outcome after

resection of olfactory groove meningiomas, particularly

in respect to olfactory function, has rarely been

performed [3, 30, 46]. We retrospectively analyzed

meningiomas with a predominant origin from the dura of

the cribriform plate with regard to clinical

presentation, different surgical approaches and

follow-up results which were treated microsurgically in

our institution.

Patients and methods

From June 1990 till June 2003, an olfactory groove

meningioma was microsurgically resected in 56

consecutive patients in our department. The medical

charts, surgical records and radiological studies were

retrospectively reviewed in these patients. Only tumours

with a primary origin from the dura of the cribriform

plate were included in this report. Lesions with a

predominant dural origin from the planum sphenoidale,

tuberculum sellae, anterior clinoidal process or orbital

roof were not considered in this series.

Radiological studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained

preoperatively in all patients and clearly demonstrated

the relationship of the tumour with the optic nerves,

chiasm and the anterior cerebral arteries (ACA). These

vessels were encased by the tumour in three patients. A

significant bifrontal or unilateral edema was displayed

on MRI in 34 patients. CT with bone algorithms,

performed preoperatively in 23 patients revealed a

hyperostosis of the crista galli or the cribriform plate

in six and erosion of the cribriform plate in four

cases. Cerebral angiography was performed regularly

early in the study period to demonstrate tumour

vascularity, provide information regarding ACA

displacement and to evaluate the possibility of

preoperative embolization. In all 23 cases studied

angiographically, the tumour was predominantly supplied

by the anterior or posterior ethmoidal branches of the

ophthalmic artery and preoperative partial embolization

was performed in two patients with occlusion of the

anterior branch of the middle meningeal artery.

Angiography is no longer performed in these tumours in

our institution. Mean maximal diameter of the tumours as

depicted from preoperative MRI was 5.2 cm (range:

2.57.5 cm).

Tumour extension and

dural attachment

As shown by preoperative MRI and confirmed

intraoperatively, the tumour was attached to the

cribriform plate, adjoining part of the planum

sphenoidale, crista galli and medial orbital roofs on

both sides in 24 patients. Tumours in these cases were

broad-based, were larger than 5.5 cm in maximal diameter

and had an almost symmetric growth on both sides. The

tumour attachment area was restricted to the cribriform

plate and adjacent part of the orbital roofs on both

sides in 19 patients.

A pure unilateral dural origin from the cribriform plate

and adjoining anterior cranial base was observed in 13

patients, on the left side in six and on the right side

in seven cases. Bilateral extension of the tumour into

the ethmoidal cells was disclosed on preoperative

coronal MRI in two cases and unilateral extension in

one. The tumour reached the nasal cavity in two

additional cases. The meningioma extended into the optic

canal on one or both sides in five patients, all of whom

had visual disturbances preoperatively.

Surgical approaches

Thirty-six patients with a bilateral tumour were

operated via a bifrontal craniotomy with opening of the

frontal sinus, double ligation and division of the

anterior end of the superior sagittal sinus with

subsequent subfrontal Fig. 3. Artists sketch showing

dural attachment of olfactory groove meningiomas. (A)

Bilateral attachment to the cribriform plate, planum

sphenoidale and orbital roofs (24 cases), (B) tumours

attached to the cribriform plate and medial orbital

roofs bilaterally (19 cases), (C) Unilateral attachment

to the cribriform plate and medial orbital roof (13

cases). Posterior extension over the tuberculum sellae

(straight arrow) was observed in four, encroachment into

the optic canal (curved arrow) in five cases removal of

the meningioma. This approach has been described in

detail [27, 28, 36]. Additionally, a bilateral tumour

was extirpated via a pterional approach in seven

patients. The contralateral tumour part was removed

after partial resection of the falx cerebri and crista

galli [15, 47]. Tumours restricted to one side were

resected through a unilateral frontal approach in four

cases, via a pterional approach in six and a lateral

supraorbital (key-hole) craniotomy in three patients

[35]. The latter approach was used in small tumours up

to 3.5 cm in diameter and was endoscopically-assisted in

one case with a deep olfactory groove. In all but three

patients were the tumour had been removed via a frontal

craniotomy the floor of the anterior cranial base was

covered with a vascularized galea-periosteal flap

reinforced with sutures and fibrin glue. A hyperostosis

of the crista galli and, or cribriform plate was removed

by drilling in 16 patients. Tumours that had invaded

into the ethmoidals or nasal cavity were removed via a

bifrontal craniotomy. This was combined with a lateral

rhinotomy performed by members of the otolaryngology

department in two cases.

Patients follow-up

All patients were followed-up with clinical examination

and MRI studies six months and one year after surgery.

Thereafter, patients were re-examined at one or two year

intervals based on each follow-up result. Postoperative

assessment of mental function was available in 25 of 31

patients with preoperative personality changes.

Olfactory function was tested semi-quantitatively before

surgery and on each follow-up examination with different

odours for each nostril separately. Preoperatively, test

results were reliably obtained in 46 patients. In the

remainder mental changes allowed only a gross

differentiation between smelling and not smelling at

best. Postoperative results of olfactory tests were

available for analysis in 41 patients. All patients with

visual disturbances had detailed pre- and postoperative

ophthalmological investigations, including visual

acuity, visual fields, fundoscopy and intraocular

pressure measurement.

Results

The 41 women and 15 men had a mean age of 51 years

(range 3074 years). The most common presenting symptoms

were mental disturbances in 22 patients (39.3%),

headache in 11 (19.6%), visual deterioration in nine

(16.1%) and anosmia in eight cases (14.3%).

References

1. Auque J, Civit T (1996) Superficial veins

of the brain. Neurochirurgie 42 Suppl 1: 88108

2. Bakay L (1984) Olfactory meningiomas. The missed

diagnosis. JAMA 25: 5355

3. Bakay L, Cares HL (1972) Olfactory meningiomas: report of

a series of twenty-five cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 26:

112

4. Bassiouni H, Hunold A, Asgari S, Stolke D (2004)

Meningiomas of the posterior petrous bone: functional

outcome after microsurgery. J Neurosurg 100: 10141024

5. Briant TDR, Zorn M, Tucker W, Wax MK (1993) The

craniofacial approach to anterior skull base tumors. J

Otolaryngol 22: 190194

6. Castillo M, Mukherji SK (1996) Magnetic resonance imaging

of the olfactory apparatus. Top Magn Reson Imaging 8: 8086

7. Chan RC, Thompson GB (1984) Morbidity, mortality, and

quality of life following surgery for intracranial

meningiomas. A retrospective study in 257 cases. J Neurosurg

60: 5260

8. Cushing H, Eisenhardt L (1938) The olfactory groove

meningiomas with primary anosmia. In: Cushing H, Eisenhardt

L (eds) Meningiomas. Charles C Thomas Springfield, pp

250282

9. Dandy WE (1925) Contributions to brain surgery: a removal

of certain deep-seated brain tumors. Ann Surg 82: 513520

10. DeMonte F (1996) Surgical treatment of anterior basal

meningiomas. J Neurooncol 29: 239248

11. Derome PJ, Guiot G (1978) Bone problems in meningiomas

invading the base of the skull. Clin Neurosurg 25: 435451

12. Durante F (1885) Estirpazione di un tumore endocranico.

Arch Soc Ital Chir 2: 252255

13. El Gindi S (2000) Olfactory groove meningioma: surgical

techniques and pitfalls. Surg Neurol 54: 415417

14. Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW (1990) Neoplasms

of the intracranial meninges. In: Youmans JR (ed)

Neurological Surgery vol 5. 3rd edn. WB Saunders,

Philadelphia, pp 32503315

15. Hassler W, Zentner J (1989) Pterional approach for

surgical treatment of olfactory groove meningiomas.

Neurosurgery 25: 942947

16. Karnofsky DA, Abelmann WH, Craver LF (1948) The use of

nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of cancer.

Cancer 1: 634656

17. Kempe LG (1968) Olfactory groove meningioma. In: Kempe

LG (ed) Operative neurosurgery, vol 1, 1st edn. Springer,

New York, pp 104108

18. Kennedy F (1911) Retrobulbar neuritis as an exact

diagnostic sign of certain tumors and abcesses in the

frontal lobes. Am J Med Sci 142: 355368

19. Keros P (1962) On the practical value of differences in

the level of the lamina cribrosa of the ethmoid. Z Laryngol

Rhinol Otol 41: 808813

20. Long DM (1989) Meningiomas of the olfactory groove and

anterior fossa. Atlas of operative neurosurgical technique,

cranial operations, vol 1. Lippincott Williams&Wilkins,

Baltimore, pp 238241

21. Maiuri F, Salzano FA, Motta S, Colella G, Sardo L (1998)

Olfactory groove meningioma with paranasal sinus and nasal

cavity extension: removal by combined subfrontal and nasal

approach. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 26: 314317

22. Mathiesen T, Linquist C, Kihlstreom L, Karlsson B (1996)

Recurrence of cranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery 39: 29

23. Mayfrank L, Gilsbach JM (1996) Interhemispheric approach

for microsurgical removal of olfactory groove meningiomas.

Br J Neurosurg 10: 541545

24. McDermott MW, Rootman J, Durity FA (1995) Subperiosteal,

subperiorbital dissection of the anterior and posterior

ethmoidal arteries for meningiomas of the cribriform plate

and planum sphenoidale: technical note. Neurosurgery 36:

12151219

25. Mirimanoff RO, Dororetz DE, Linggood RM, Ojemann RG,

Mortuza RL (1985) Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and

progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg

62: 1824

26. Obeid F, Al-Mefty O (2003) Recurrence of olfactory

groove meningiomas. Neurosurgery 53: 534543

27. Ojeman RG (1996) Supratentorial meningiomas: clinical

features and surgical management. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary

SS (eds) Neurosurgery, vol 1. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp

873890

28. Ojemann RG (1991) Olfactory groove meningiomas. In:

Al-Mefty O (ed) Meningiomas. Raven Press, New York, pp

383393

29. Olivecrona H (1967) Surgical treatment of intracranial

tumors. In: Olivecrona H et al (eds) Handbuch der

Neurochirurgie, vol. 4. Springer, Berlin, pp 160167

30. Passagia JG, Chirossel JP, Favre JJ, Gray E, Reyt E,

Righini C, Chaffanjon P (1999) Surgical approaches to the

anterior fossa, and preservation of olfaction. Adv Tech

Stand Neurosurg 25: 195241

31. Persky MS, Som ML (1978) Olfactory groove meningioma

with paranasal sinus and nasal cavity extension: a combined

approach. Otolaryngology 86: 714720

32. Poppen JL (1964) Operative techniques for removal of

olfactory groove and suprasellar meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg

2: 17

33. Quest DO: Meningiomas (1978) An update. Neurosurgery 3:

219225

34. Ransohoff J, Nockels RP (1993) Olfactory groove and

planum meningiomas. In: Apuzzo MLJ (ed) Brain surgery.

Complication avoidance and management, vol. 1. Churchill

Livingstone, New York, pp 203219

35. Reisch R, Perneczky A, Filippi R (2003) Surgical

technique of the supraorbital key-hole craniotomy. Surg

Neurol 59: 223227

36. Samii M, Ammirati M (1992) Olfactory groove meningiomas.

In: Samii M (ed) Surgery of the skull base: meningiomas.

Springer, Berlin, pp 1525

37. Seeger W (1983) Microsurgery of the cranial base.

Springer, New York

38. Sekhar LN, Tzortzidis F (1999) Resection of tumors by

the frontoorbital approach. In: Sekhar LN et al (eds)

Cranial microsurgery: approaches and techniques. Thieme, New

York, pp 6175

39. Simpson D (1957) The recurrence of intracranial

meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 20: 2239

40. Solero CL, Giombini S, Morello G (1983) Suprasellar and

olfactory meningiomas: report on a series of 153 personal

cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 67: 181194

41. Symon L (1977) Olfactory groove and suprasellar

meningiomas. In: Krayenbhuhl H et al (eds) Advances and

technical standards in Neurosurgery, vol 4. Springer, Wien

New York, pp 6791 120 H. Bassiouni et al.

42. Teonnis W (1938) Zur Operation der Meningeome der

Siebbeinplatte. Zentralbl Neurochir 1: 17

43. Tsikoudas A, Martin-Hirsch DP (1999) Olfactory groove

meningiomas. Clin Otolaryngol 24: 507509

44. Turazzi S, Cristofori L, Gambin R, Bricolo A (1999) The

pterional approach for the microsurgical removal of

olfactory groove meningiomas. Neurosurgery 45: 821826

45. Van Toller S (1999) Assessing the impact of anosmia:

review of a questionnaires findings. Chem Senses 24:

705712

46. Welge-Luessen A, Temmel A, Quint C, Moll B,Wolf S,

Hummel T (2001) Olfactory function in patients with

olfactory groove meningioma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

70: 218221

47. Yasargil MG (1996) Microneurosurgery of CNS Tumors, vol

IVB. Thieme, New York, pp 140141

|

Comments

|

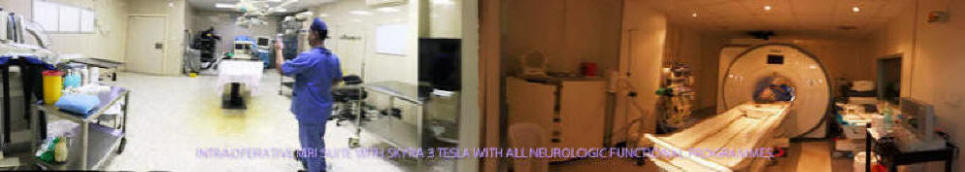

Intraoperative navigation will ameliorate such

events, and confirm the necessity for such technology. Real-time

intraoperative navigation is costly and commercially inapplicable

for private sector, and must be modified to be used for all surgical

disciplines and to have neurophysiologic monitoring added to the

navigation system merged with the visual data in real time.

|

|

MRI of the brain done 01-January-2005 confirming the total

resection of the tumor with mild malacia of the left frontal lobe

due to to pressure effect of the missed right occipito-parietal

extradural hematoma. |

Postoperative MRI after 3 years showing complete resection and no

recurrence.

Olfactory groove meningiomas:

functional outcome

in a series treated microsurgically

H. Bassiouni, S. Asgari,

and

D. Stolke

Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Essen,

Essen, Germany

|

Background

A systematic investigation of long-term follow-up

results after microsurgical treatment of patients harbouring

an olfactory groove meningioma, particularly with regard to

postoperative olfactory and mental function, has rarely been

performed. We reassessed a series of patients treated

microsurgically for an olfactory groove meningioma in regard

to clinical presentation, surgical approaches and long-term

functional outcome. Method. Clinical, radiological and

surgical data in a consecutive series of 56 patients

suffering from olfactory groove meningioma were

retrospectively reviewed.

Findings. Presenting symptoms of the 41 women and 15 men

(mean age 51 years) were mental changes in 39.3%, visual

impairment in 16.1% and anosmia in 14.3% of the patients.

Preoperative neurological examination revealed deficits in

olfaction in 71.7%, mental disturbances in 55.4% and reduced

vision in 21.4% of the cases. The tumour was resected via a

bifrontal craniotomy in 36, a pterional route in 13, a

unilateral frontal approach in 4 and via a supraorbital

approach in 3 patients. Extent of tumour resection according

to Simpsons classification system was grade I in 42.9% and

grade II in 57.1% of the cases. After a mean followup period

of 5.6 years (range 113 years) by clinical examination and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 86.8% of the patients

resumed normal life activity. Olfaction was preserved in

24.4% of patients in whom pre- and postoperative data were

available. Mental and visual disturbances improved in 88 and

83.3% of cases, respectively. Five recurrences (8.9%) were

observed and had to be reoperated.

|

|

Conclusions

Frontal approaches allowed better resection of

tumours with gross infiltration of the anterior cranial

base, tumours extending into the ethmoids or nasal cavity

and in cases with deep olfactory grooves. Preservation of

olfaction should be attempted in patients with normal or

reduced smelling preoperatively. |

|

Introduction

Meningiomas of the midline anterior skull base

include tumours originating from the dura of the cribriform

plate, planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae and account

for about 10% of all intracranial meningiomas [41]. For

clinical, radiological and surgical purposes true olfactory

groove meningiomas, i.e. tumours originating from the dura

between the crista galli and the frontosphenoid suture

should be differentiated from planum sphenoidale and

tuberculum sellae meningiomas [8, 32]. Tumours arising from

the latter sites usually come to clinical attention at an

early stage with visual deterioration, while this is a late

feature in olfactory groove meningiomas which usually remain

clinically quiescent during the early phase of growth.

Anatomically, olfactory groove meningiomas arise from the

weakest part of the skull base, the cribriform plate, which

makes them prone to infiltrate the underlying bone and

extend into the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. This is

a rare feature in planum sphenoidale or tuberculum sellae

meningiomas.

A systematic assessment of functional outcome after

resection of olfactory groove meningiomas, particularly in

respect to olfactory function, has rarely been performed [3,

30, 46]. We retrospectively analysed meningiomas with a

predominant origin from the dura of the cribriform plate

with regard to clinical presentation, different surgical

approaches and follow-up results which were treated

microsurgically in our institution. |

|

Patients and methods

From June 1990 till June 2003, an olfactory

groove meningioma was microsurgically resected in 56

consecutive patients in our department. The medical charts,

surgical records and radiological studies were

retrospectively reviewed in these patients. Only tumours

with a primary origin from the dura of the cribriform plate

were included in this report. Lesions with a predominant

dural origin from the planum sphenoidale, tuberculum sellae,

anterior clinoidal process or orbital roof were not

considered in this series. |

|