Anatomy

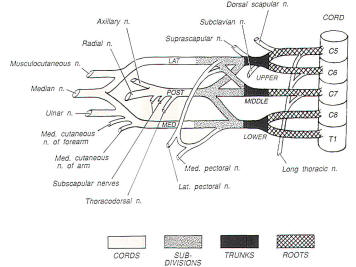

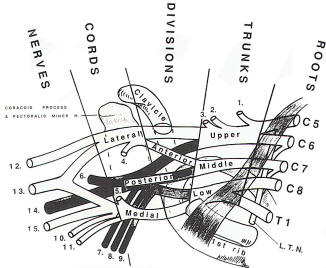

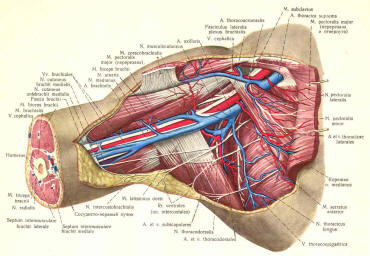

A review of the anatomy of the brachial plexus is necessary before a discussion of surgical approaches can be made. The brachial plexus is composed of ventral rami of C5, C6, C7, C8, and Th1. The plexus lies in the posterior triangle of the neck between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius muscles. It passes deep to the clavicle, a structure often conveniently used as a landmark in plexus surgery. The distal plexus surrounds the axillary artery, which is also an important operative landmark.

The structure of the plexus has many variations, but the basic outline is as follows: 1. Ventral C5and C6 roots become the upper trunk. The C7 ramus forms the middle trunk and C8 and Th1 rami form the lower trunk. In addition to the main terminal branches, numerous branches exit the plexus at other levels. Often in traumatic injuries, many of the smaller branches were destroyed by the traumatic event or result from post-traumatic scarring.

Branches from Rami and Trunks 1. The phrenic nerve receives contributions from the C5 ramus. The phrenic nerve then travels along the anterior surface of the scalenus anterior muscle. This nerve is often visualized early in an anterior dissection of the brachial plexus. 2. The long thoracic nerve arises from the C5-7 anterior and rami to innervate the serratus anterior muscle. 3. The dorsal scapular nerve arises from the C5 ramus and innervates the rhomboid muscles as well as the levator scapulae muscle. 4. The nerve to the subclavius muscle is a branch of the upper trunk. 5. The suprascapular nerve is a relatively large nerve that exits the upper trunk and travels in a lateral direction to innervate the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles. Branches from Cords

Lateral Cord

The lateral pectoral nerve innervates the pectoralis major muscle.

Medial Cord

1. The medial pectoral joins the lateral pectoral nerve to innervate the pectoral muscles. 2.The medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerves supply cutaneous sensation to the arm and forearm. These nerves are important in that they can be sacrificed for nerve cable grafting if necessary with the only deficit being loss of sensation to the skin in a relatively insignificant distribution.

Posterior Cord 1.The subscapular nerve innervates the subscapulous muscle and the teres major muscle. This nerve often leaves the cord in two branches

|

| |||||

| ||||||

Operative Approaches

The two fundamental operative approaches to the brachial plexus are the anterior and posterior approaches. The anterior approach may be divided into a supraclavicular and an infraclavicular exposure, which often are combined to expose the entire plexus. The posterior approach is used infrequently because of fewer indications and greater operative complications; however, it may be helpful in isolated cases.

General Considerations

Since it is important to be able to observe the upper extremity during the entire procedure, either the entire arm should be included in the surgical field or draped so that the major muscle groups can be palpated during the operation. The position of the patient is important and is discussed along with each operative approach here. The choice of anesthetic agents depends on the need for intraoperative electrodiagnostic studies. Since these studies are usually required in trauma, tumor, and the vast majority of brachial plexus stretch injury cases, the anesthetic technique should involve no agents that interfere with nerve action potentials. Pharmacologic muscle paralysis is contraindicated. |

| |||||

Nitrous oxide, narcotics, and inhalation agents are the agents of choice. If it is necessary to graft gaps in plexus elements, both legs should be prepared for sural nerve harvesting prior to the operation. Although the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve to the forearm may be harvested, it is often not long enough. Magnification may be used for the surgical dissection and the suturing of grafts. Either surgical loupes or the operating microscope can be used, depending on the preference of the surgeon. Loupes with 3.5 X magnification are often satisfactory for most purposes. Finally, the plexus surgeon must possess basic vascular surgical skills in his or her armamentarium. Post-traumatic brachial plexus explorations often involve dissecting through scar tissue around vascular structures such as the axillary artery and vein. Following months of healing, both vascular and neural structures may be embedded in thick scar. The vascular and plexus elements, therefore, need to be separated during the operative procedure. In this situation, it may be necessary to repair vascular injuries that may arise. If this skill is not possessed by the plexus surgeon, a vascular surgeon should be available to assist in the operation, if needed. Once the plexus is exposed, meticulous dissection must be performed to expose all neural and vascular elements. Small branches of the plexus must be identified and reserved. Often in delayed traumatic explorations, all elements will be encased in scar tissue. Sharp dissection is the best way to dissect the elements from the scar tissue. When the elements are exposed, Penrose drains may be placed around the large neural elements in order to retract and isolate the elements. Smaller nervous structures may be retracted using smaller vessel loops. This will allow isolation of single elements to facilitate the electrophysiologic testing.

Anterior Approach

The anterior approach to the brachial plexus is the most common approach and can be used in most circumstances. The entire plexus, from nerve roots to terminal branches can be exposed using this technique. The patient is positioned supine on the operating table. A roll is placed under the ipsilateral shoulder and the head is slightly rotated toward the contralateral side. The ipsilateral arm is best placed on an arm board laterally. This will allow the arm to be either palpated under sterile drapes or visualized if included in the operative field. Also, this arrangement will allow one surgeon to stand next to the neck above the arm board and the other surgeon to stand in the apex between the arm and the chest. The neck, shoulder, axilla, and chest wall should be prepared along with both legs if a grafting procedure is anticipated.

Supraclavicular Approach

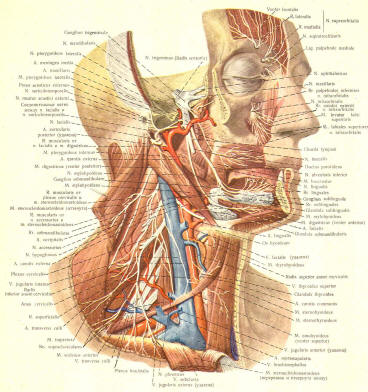

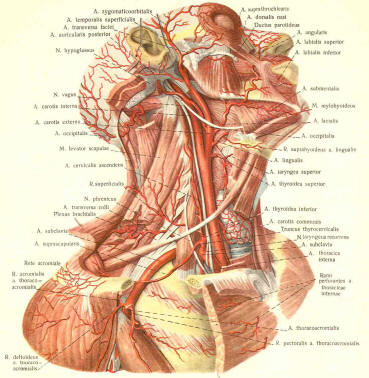

An incision is made along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. This incision should be carried down across the clavicle and may be extended farther if an infraclavicular approach is required. The skin is opened and the platysma muscle, which is enveloped by the superficial fascia of the neck, is visualized. It is useful to split the muscle and later close the platysma muscle as a separate layer if possible, as this often will allow a good cosmetic closure of the neck. The external jugular vein is often found under the platysma muscle and can be ligated if needed. The sternocleidomastoid muscle may be detached from its lateral attachment to the clavicle. The spinal accessory nerve crosses the sternocleidomastoid muscle and must be preserved. This nerve is often located more cephalad than the operative exposure.A deep fascial layer separates the superficial portion of the posterior triangle from its deep portion. This contains the brachial plexus. The first structure seen will be the omohyoid muscle, which may be divided between two sutures and retracted. This muscle can be reapproximated when closing. The transverse cervical artery and vein can be ligated or retracted as necessary. The brachial plexus is observed between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius muscle. The phrenic nerve, which is usually found on the anterior surface of the scalenus anterior muscle, needs to be preserved. Dissection now may be carried in a medial direction by cutting fibers of both scalenus muscles to fully expose the plexus and the roots. Care must be taken to avoid injury to vascular structures other than the transverse cervical vessels. Important vascular structures include the subclavian artery and vein inferior to the plexus and the vertebral artery located in front of the scalenus anterior muscle and medial to the phrenic nerve. The thoracic duct can be sealed off with cautery if a lymphatic leak is encountered. The supraclavicular approach will expose the nerve roots as they exit the neuroforamina, become trunks, and divide. If the cords need to be exposed, the skin incision can be extended into an infraclavicular approach

Infraclavicular Approach

The supraclavicular incision may be continued over the clavicle or the incision started at the clavicle if a supraclavicular incision was not made. The incision should extend laterally in the deltopectoral groove, which usually can be palpated. After the skin and the subcutaneous tissue are incised, the incision of the fascial plane over the deltoid and pectoralis muscles exposes the cephalic vein. Blunt dissection between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles is performed with gentle retraction of the cephalic vein. Self-retaining retractors are placed between the two muscles. The lateral and medial pectoral nerves are then visualized. The nerves can be sacrificed, if needed, to expose the plexus. The pectoralis minor muscle is located below these muscles and the pectoral nerves. This muscle should be ligated between two sutures and cut. This muscle must not be reapproximated. Constriction of a repaired plexus may result. Dissection toward the clavicle will expose the subclavius muscle on the inferior surface of the clavicle. This muscle can be sacrificed if necessary, especially when dissection must be done under the clavicle. Often, numerous small vessels are in this area. They must be cauterized or profuse bleeding will occur. Under normal conditions, the first neural element visualized is the lateral cord. Deeper dissection will reveal the other cords and the axillary artery. The cords are named for their anatomic relationships to the artery, however, with posttraumatic scarring, these relationships often are obliterated. Distal dissection that identifies the major branches may be necessary to allow backtracking to the cords in order to label the cords.

Combined Approach

The supraclavicular and infraclavicular approaches can be combined or either approach extended if necessary. In the past, the clavicle was often resected followed by internal fixation during the closure of the procedure. Recently more and more plexus surgeons are not resecting the clavicle due to the higher-thanexpected incidence of nonunion. The skeletonized clavicle has a poor vascular supply and often does not heal well. If the clavicle has been fractured by previous trauma, it is easy to remove loose pieces to gain more exposure for the nerve dissection, but if the clavicle is intact, it should be retracted. By wrapping an unfolded surgical sponge around the clavicle, clamping the sponge, and pulling on the clamp, the clavicle can be retracted in both directions. This provides adequate exposure in nearly all cases.

Closure

Following a supraclavicular exposure, the omohyoid muscle can be reapproximated. The platysma is closed. This will pull most of the neck structures together. This is followed by closing the subcutaneous tissue and the skin closure. Following an infraclavicular approach, the pectoralis minor muscle should not be resutured; however, fascia over the deltoid and pectoral muscles is sutured, followed by closure of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.

Posterior Approach

The posterior approach was used originally in the treatment of empyema in the preantibiotic era. Recently it has been used in selected cases of brachial plexus pathology. The approach is useful for proximal plexus lesions involving roots and trunks. It is also a useful approach in patients who have had a prior anterior plexus operation or who have undergone radiation therapy of the anterior chest wall. Finally, it is useful for the treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome in patients who have had a previous operation, especially a transaxillary approach. The patient is positioned prone on the operating table with the head turned toward the contralateral side. The ipsilateral arm is abducted and flexed at the shoulder. The arm is then flexed at the elbow . The incision is made midpoint between the spinous processes and medial border of the scapula . The patient's position causes external rotation of the scapula and affords more space between the scapula and spine. The incision can be extended onto the neck if further exposure is needed. The trapezius muscle is divided along the length of the incision. The muscle can be divided between clamps, and the fibers can be sutured prior to the clamps removal. This will allow reapproximation of the muscle at the time of closure. Under the trapezius muscle in a cephalad to caudad direction, the levator scapulae, the rhomboid minor, and the rhomboid major muscles are observed. These muscles also can be divided by a clamp and tagged with a suture to facilitate closure. A self-retaining retractor is then placed between the ventral scapula and spinous processes. Ribs are easily palpated at this time. The second rib is identified and may need to be removed along its medial aspect to identify the first rib. The goal is resection of the first rib and its periosteum from the transverse process of T1 to the costoclavicular ligament. The first rib has been observed to regenerate if the periosteum has not been removed. After the first rib has been removed, the scalenus posterior and medius muscles will be identified and can be removed. At this point, the brachial plexus trunks will be identified. The subclavian artery and vein will be inferior to the lower trunk and should be protected. The trunks can be followed laterally to the division level or medially to the root level. Often, this approach can result in a small pleural leak, and a chest tube may need to be inserted. Closure of this exposure involves reapproximating the cut muscle groups. This muscle cutting provides the major morbidity of this procedure. Complications include occasional winged scapula and decreased shoulder strength, especially if a prior shoulder injury has caused muscle weakness.