|

In this section

the emphasis is directed to other entrapment

syndromes.

Etiology

Etiology

The compressed segment is in a

specific location on the nerve as determined by the

local anatomy, i.e. where the nerve traverses a

tunnel bound by bone and fibrous tissue or where the

nerve passes from one compartment to another.

Changes in the tissue consistency that surrounds the

nerve can precipitate entrapment. Trauma with direct

injury or callus formation after fracture also has

been implicated. Systemic diseases that have been

associated with entrapment include hypothyroidism,

acromegaly, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis,

giant-cell arteritis, and amyloidosis. An anatomic

variant, such as an accessory muscle, arterial

aneurysm, or congenitally small tunnel, can

precipitate an entrapment neuropathy as well.

Compression of the posterior interosseous nerve, for

example, has been described with hemihypertrophy and

with a lipoma in the region of the elbow. There are

cases with compression of the median nerve by a

lipoma in the deep palmar space and compression of

the ulnar nerve by a schwannoma in the cubital

tunnel.

Occupational causes of neuropathy are

common. Carpal tunnel syndrome has been reported as

an overuse syndrome in persons who employ sign

language for the deaf. The carpal tunnel syndrome

has been observed in patients with paraparesis who

use crutches for walking. Compression of the ulnar

nerve in Guyon's canal is seen in cyclists.

Compression of the ulnar nerve is legendary in

patients who spend long hours leaning their elbows

on bars.

The probable cause of entrapment

neuropathy is a decrease in the neural blood supply.

The nerve receives its blood supply from the

mesoneurium, which is flexible and permits

continuing perfusion as the extremity moves. Venous

obstruction caused by compression increases

intrafascicular pressure. This, in turn, decreases

perfusion, which leads to edema. A vicious cycle

ensues. An ingrowth of fibroblasts and scar

ultimately results. This adds to the vicious cycle

of worsening hypoxia. Diabetes, which compromises

the blood supply, places the nerve at an additional

risk of compression and repetitive injury.

Compression and atrophy can be so long-standing that

end organ fibrosis may result. In this situation,

decompression of the nerve will not improve the

neurologic symptoms.

The electrodiagnostic findings in any

entrapment neuropathy depend on a number of

variables including (1) the timing of the study, (2)

the severity of the injury, and particularly (3) the

relative amounts of demyelination and axonal loss.

In the experience of a competent

electrodiagnostician, normal findings are rarely

identified as abnormal. Conversely,

electrodiagnostic evaluations may be inadequate to

identify minor injuries to nerves. This situation

can occur in proximal demyelinating lesions when

conduction studies cannot be obtained above and

below the suspected lesion due to technical

limitations. In addition, false-negative results or

inconclusive results may occur because of premature

testing. Complete expression of an abnormality may

require up to 7 days for motor nerve conduction. 9-

10 days for sensory conduction, and 3 weeks for

needle examination of muscle; however,

electrodiagnostic studies are useful to diagnose

other syndromes, such as proximal lesions, multiple

lesions, or lesions that accompany diabetes

mellitus.

Differential

Diagnosis

Differential

Diagnosis

Strict criteria should be used to

diagnose entrapment neuropathies. It is regular to

see patients with spondylotic myelopathy and

radiculopathy who have undergone unnecessary carpal

tunnel surgery. The peak age for both conditions is

the same, and many of these patients have electrical

evidence of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Radiculopathy involving the C8 nerve

root can be confused with ulnar neuropathy. When the

patient has thenar atrophy as well as involvement of

the ulnar nerve, a C8 nerve root lesion should be

suspected strongly. A double crush syndrome is when

cervical or thoracic outlet compression worsens

median or ulnar entrapment. It is unusual for a

patient to have more than one lesion. A high index

of suspicion, the unique symptoms and physical

findings, the results of electrodiagnostic studies,

and, when necessary, cervical spine imaging should

lead to the correct diagnosis.

Internal Neurolysis

Internal Neurolysis

The value of internal neurolysis at

the time of decompression has long been debated.

Mackinnon and colleagues documented an improved

electrical and morphologic recovery with neurolysis

compared to decompression alone in a rat model. In a

clinical paper, however, Mackinnon and colleagues

demonstrated that although neurolysis is a safe

procedure, it does not provide clinical benefit in

patients who have had carpal tunnel surgery.

Neurolysis of a nerve whose diameter is diminished

by a circumferentially thickened and scarred

epineurium may improve nutrition and permit nerve

expansion during healing. Nevertheless, neurolysis

is not necessary for all patients undergoing carpal

tunnel surgery or with compressed nerves.

Performance of internal neurolysis in every carpal

tunnel operation courts disaster. The decision on

whether or not to perform a neurolysis depends on

the observation of the nerve in the operating room.

If the nerve remains narrowed after the surgical

decompression or if intraneural scarring is present,

neurolysis should be done. Patients who present with

recurrent symptoms could have neurolysis. After

neurolysis, the fascicles, even if atrophic, will be

obvious and not hidden in thick epineurium.

Median Nerve

Median Nerve

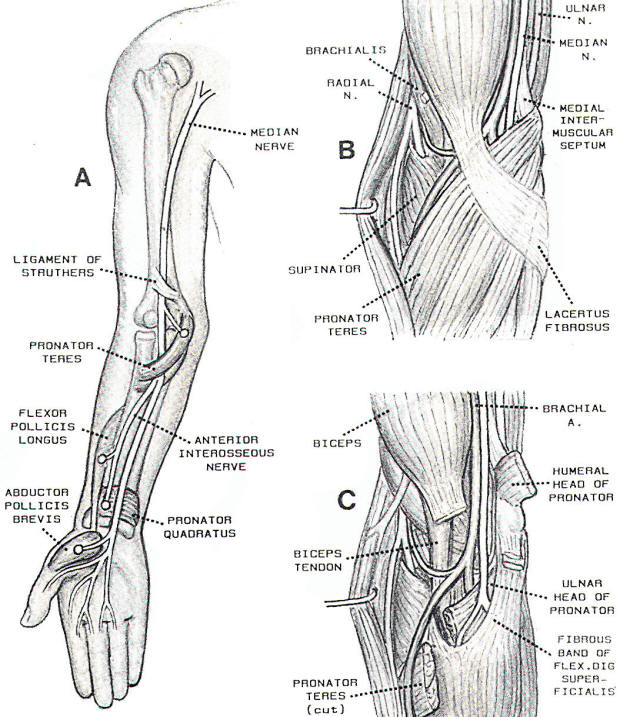

The more proximal median compression

syndromes can produce pain, neurologic deficit, or

both. The compression can occur above the elbow at

the ligament of Struthers or below the elbow by the

pronator teres muscle (Figure 1A,B,C).

Fig-1

Entrapment at

Ligament of Struthers

Entrapment at

Ligament of Struthers

The ligament of Struthers, which

should not be confused with the arcade of Struthers

(which produces ulnar neuropathy), is located 5 cm

proximal to the medial epicondyle. The median nerve

and brachial artery both pass beneath this ligament.

Nerve compression at the ligament of Struthers

usually produces a syndrome of pain and local

tenderness. The anterior interosseous nerve branch

of the median nerve can be compressed at the

ligament of Struthers, with resultant motor

neuropathy. This phenomenon is unusual. The

electrodiagnostic findings demonstrate a reduced or

absent median sensory potential. With a

predominantly demyelinating lesion, conduction

velocity may be slowed across the involved segment

with a normal conduction velocity below. Conduction

study motor amplitudes will be reduced after axon

loss, regardless of the site of stimulation. With

demyelination, however, motor amplitudes are

abnormal only with stimulation above the site of the

lesion. With any amount of axon loss, denervation

will be evident in all median innervated muscles of

the hand and forearm. Section of the ligament

effectively relieves symptoms.

Pronator Syndrome

Pronator Syndrome

The pronator syndrome is

characterized by mild to moderate pain in the

forearm. The pain increases with movement of the

elbow, with repeated supination and pronation,

and with repeated use of the grip. Loss of

dexterity in the hand, mild weakness, and median

nerve paresthesia occur. Numbness may be

present, not only in the fingers, but also in

the thenar region of the palm because of

involvement of the palmar cutaneous nerve that

branches distal to the site of compression.

These symptoms resemble carpal tunnel syndrome,

but the symptoms of paresthesia while sleeping

are absent. The pain in the forearm and the

local tenderness can be reproduced by resisted

pronation. Tinel's sign may be present over the

nerve.

The anatomic level of compression

is within the substance of the pronator teres

muscle. The median nerve with the brachial

artery lies between the two heads of the

pronator teres and passes deep to the fibrous

origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis

muscle. Compression may be caused by the

thickened lacertus fibrosus, by a hypertrophied

pronator muscle, or by a tight fibrous band of

the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle.

Results of electrodiagnostic studies are often

normal. When results are abnormal, they parallel

the findings in patients with the ligament of

Struthers syndrome except that no denervation is

present in the pronator teres muscle.

Treatment of patients with the

pronator syndrome is initially conservative with

administration of anti-inflammatory medication

and use of splints. An attempt is made to

eliminate precipitating events. Should these

measures be ineffective, surgery should provide

good results. The lacertus fibrosus is released

and the median nerve is translocated to a

subcutaneous position anterior to the pronator

teres muscle. The nerve should be exposed from

the distal upper arm to the middle forearm. The

median nerve and its major branches should be

visualized. Care should be taken to preserve the

branches of the medial cutaneous nerve of the

forearm. Injury to this nerve can produce a

painful neuroma.

Anterior

Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

Anterior

Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

The anterior interosseous nerve

separates from the main median nerve

approximately 8 cm distal to the lateral

epicondyle. It gives off a sensory branch to the

wrist joint and provides motor innervation to

the flexor pollicis longus muscle, the flexor

digitorum profundus muscle of the index and

middle fingers, and the pronator quadratus

muscles. The site of compression is slightly

more distal in the mass of the pronator teres

muscle than that for the pronator syndrome. The

compression is caused by the tendinous origin of

the deep head of the pronator teres muscle,

which crosses the anterior interosseous nerve at

its origin from the parent median nerve. An

enlarged bicipital bursa has also been described

as the causative agent. Whereas pain and

tenderness are present in the forearm of

patients with the anterior interosseous nerve

syndrome, the predominant symptoms and objective

findings are motor. When untreated, the pain

often resolves. Motor loss then follows.

Characteristically, an abnormal pinch is

produced because of the inability to flex the

interphalangeal joint of the thumb.

Results of nerve conduction

studies typically are normal in patients with

the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome.

Results of needle electromyography indicate

denervation restricted to the three muscles

innervated by the nerve. Occasional patients may

present clinically with the anterior

interosseous nerve syndrome and with

electrodiagnostic proof of a more proximal

lesion of the median nerve. Presumably, the

fascicles destined to become the anterior

interosseous nerve are affected more selectively

in this situation. The surgical exposure for

patients with this syndrome is similar to that

described for the pronator syndrome.

Ulnar Nerve

Ulnar Nerve

In addition to the ulnar nerve

compression found at the cubital tunnel, ulnar

neuropathies can be caused by compression at the

arcade of Struthers and in Guyon's canal.

Because the sensory symptoms are located on the

medial aspect of the hand and arm, it is

necessary to be certain that the condition is

not caused by a C8 nerve root or lower brachial

plexus lesion.

Arcade of

Struthers

Arcade of

Struthers

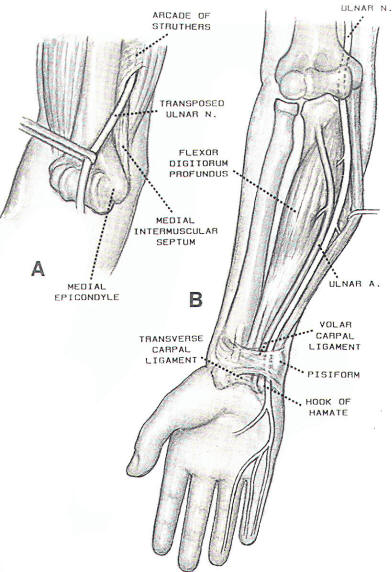

The arcade of Struthers (Figure

2A) is located where the ulnar nerve passes

through the medial intermuscular septum into the

posterior compartment. The arcade is a fibrous

septum that is located 8 cm proximal to the

medial epicondyle. It is present in only 70% of

patients. The arcade of Struthers is rarely a

site of primary compression. It may, however,

become important following an anterior

transposition of the nerve as a proximal tether

impinging on the nerve. It is important to

release the band when transposing the nerve to

prevent this secondary compression.

Guyon's Canal

Guyon's Canal

Guyon's canal is found on the

medial aspect of the wrist (Figure 2B). The

anterior border of Guyon's canal is the volar

carpal ligament, whereas the posterior border is

the transverse carpal ligament. Within the

canal, the ulnar nerve runs with the ulnar

artery and vein and divides into motor and

sensory branches. The distal lesion affects only

the motor branch, and the more proximal lesion

affects both the motor and the sensory branch.

Because the motor branch is deeply placed and

tethered as it passes around the hook of the

hamate bone, it is prone to compressive lesions.

Spaceoccupying lesions, such as ganglia,

produce compression as does chronic occupational

trauma in cyclists and in persons who use their

hands as hammers. Space-occupying lesions may be

encountered in patients with fracture of the

pisiform bone or hook of the hamate bone.

Pure motor paresis produces a

claw hand as a result of intrinsic weakness and

separation of the fourth and fifth fingers

(Wartenberg's sign). Mixed nerve compression

produces paresthesia and sensory loss as well as

the typical clawhand.

Electrodiagnostic findings again

depend on whether the lesion is predominantly

axonal or demyelinating. With demyelinating

lesions, slowing of motor and sensory latencies

across the wrist may be expected, particularly

when sensory studies are performed by the palmar

technique, and the motor conductions are

performed while recording from the first dorsal

interosseous muscle. In axonal lesions, motor

and sensory amplitudes are reduced and

denervation is found in the ulnar muscles of the

hand. Reduced amplitude of the dorsal cutaneous

branch of the ulnar nerve or denervation in the

ulnar muscles of the forearm implies the

existence of a lesion proximal to the wrist.

When the patient's condition does

not respond to the use of splints and the

administration of anti-inflammatory medications,

the canal should be explored. Surgery in this

instance usually is indicated earlier than in

patients with other compression neuropathies

because of the motor involvement. Both

superficial and deep branches of the nerve

within the canal should be explored carefully.

Any mass within the canal, such as a ganglion

cyst or a displaced hook of the hamate bone,

should be removed.

Fig-2:

Radial Nerve

Radial Nerve

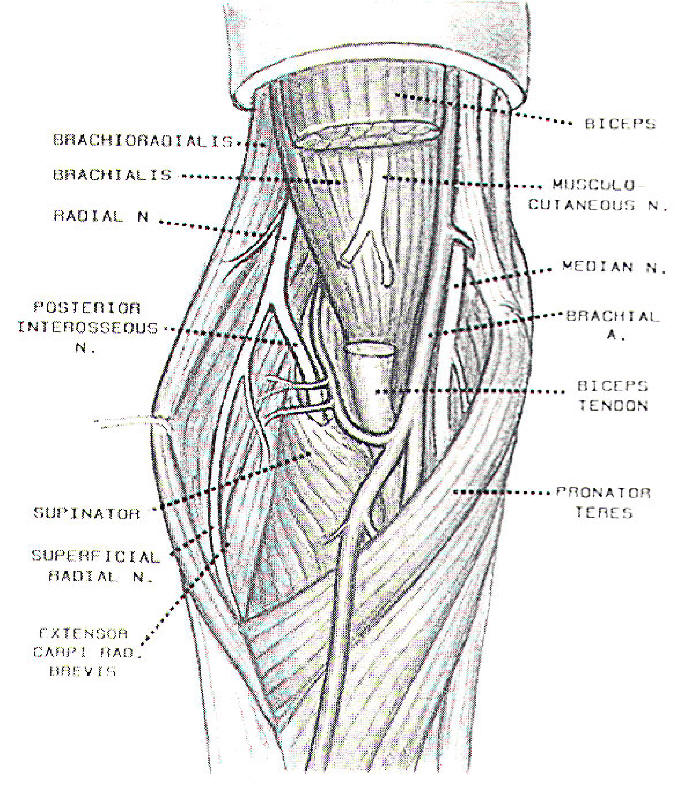

Compression neuropathies of the

radial nerve produce clinical syndromes dependent on

the level of compression (Figures 3 and 4). The

lesion in the proximal arm is rarely spontaneous but

is associated with trauma, most commonly fracture of

the humerus. "Saturday night palsy" results from

compression of the radial nerve when the patient

sleeps heavily with the posterior arm resting

against a firm edge. The patient presents with

wristdrop and an inability to extend the fingers.

This condition usually is associated with sensory

loss because of the high level of the nerve injury.

Of patients who present with radial nerve palsy. 80%

recover spontaneously; therefore, exploration is not

performed early in most instances. If the palsy is

associated with fracture of the humerus, however,

early surgery may be appropriate. When the nerve is

explored, it should be freed from the bone fragments

or callus and reanastomosed when divided.

In patients with demyelinating

lesions of the radial nerve at the middle to

proximal humerus, results of conduction studies

distal to the lesion are normal. Studies performed

proximal to the lesion will show a reduced or slowed

motor response compared with stimulation distal to

the lesion. In patients with axonal lesions, radial

motor and sensory amplitudes are reduced and

denervation is found in all radial muscles

innervated distal to the triceps muscle. Changes on

electromyography are not observed until 3 weeks

after the injury.

The radial nerve curves around the

posterior humerus in the spiral groove and enters

the anterior aspect of the arm, 10 cm proximal to

the lateral epicondyle, by passing through the

lateral intermuscular septum. The radial nerve

passes anterior to the radiohumeral joint where it

divides into superficial and deep branches. The

superficial branch proceeds distally, deep to the

brachioradialis muscle, to provide sensation to the

dorsum of the first web space in the hand. The deep

branch spirals around the neck of the radius,

passing between the two heads of the supinator

muscle, to enter the posterior aspect of the arm as

the posterior interosseous nerve (Figure 4A). The

deep branch supplies the extensor muscles of the

wrist, hand, and thumb except for the extensor carpi

radialis longus muscle, which is innervated by a

branch from the radial nerve before it enters the

supinator muscle.

|

|

| Fig-3 |

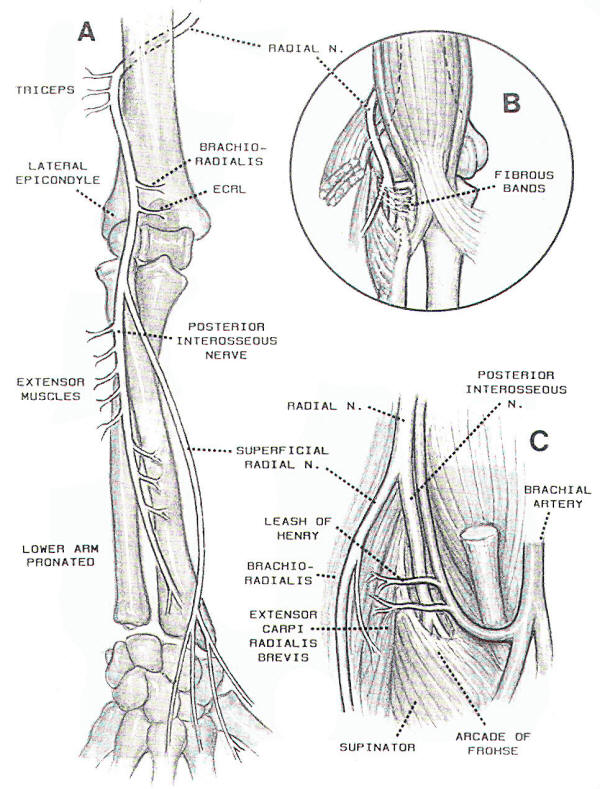

Fig-4 |

Radial Tunnel

Syndrome

Radial Tunnel

Syndrome

The clinical syndrome associated with

compression of the deep branch of the radial nerve

has been called the radial tunnel syndrome. It may

be confused with tennis elbow. The radial tunnel

syndrome, however, produces a deep somatic ache in

the extensor muscles, usually exacerbated by

exercise, without sensory or motor symptoms. Four

potential sites of compression exist: (1) by fibrous

bands anterior to the radial head (Figure 4B), (2)

by vessels of the leash of Henry that pass over the

radial nerve to supply the brachioradialis muscle,

(3) by the tendinous margin of the extensor carpi

radialis brevis muscle, and (4) by the arcade of

Frohse, which is the sharp ligamentous margin of the

superficial head of the supinator muscle (Figure

4C). The latter is the most common site of

compression. This sharp edge is not present in the

fetus. It is fibrotendinous in 30% of limbs. The

arcade of Frohse forms in response to repeated

rotary movements of the arm. This syndrome in the

dominant arm in 89% of patients. Most patients have

a history of repetitive trauma, such as is observed

in bricklayers, pipe fitters, machine operators,

orchestra conductors, and tennis players. Other

causes of compression may be tumor, lipoma, synovial

proliferation in rheumatoid arthritis, or fracture

of the head of the radius.

Tennis Elbow

Tennis Elbow

In discussing the broad diagnosis of

tennis elbow, a range of disorders from lateral

epicondylitis to severe extensor weakness, they

included the radial tunnel syndrome. On examination,

tenderness is present over the lateral epicondyle of

the humerus or just distal to the radial head where

the nerve travels into the supinator muscle. A

typical increase in pain occurs when extension of

the middle finger is resisted. This maneuver will

tighten the origins of the extensor carpi radialis

brevis muscle and further compress the nerve. Injury

to the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis

tendon at the lateral epicondyle is related to

epicondylitis-the classic tennis elbow. Local

injection with lidocaine and a corticosteroid

provides only temporary relief of symptoms.

Results of electrodiagnostic studies

may demonstrate delays in motor latencies from the

spiral groove to the medial border of the extensor

digitorum communis muscle, but they are frequently

normal. For patients whose neuropathy does not

respond to avoidance of trauma, use of splints, and

administration of anti-inflammatory medications,

surgical exploration with decompression of the

superficial radial nerve is indicated.

Posterior

Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

Posterior

Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

The syndrome of the posterior

interosseous nerve differs from the radial tunnel

syndrome in that the predominant symptoms and

findings are motor rather than pain or sensory loss.

The arcade of Frohse is the major constricting

structure. Severe weakness of the radial innervated

muscles exists with inability to extend the fingers

at the metacarpophalangeal joint. The wrist

dorsiflexes in a dorsoradial direction because of

paralysis of the extensor carpi ulnaris and the

extensor digitorum communis muscles. The

brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus,

extensor carpi radialis brevis, and supinator

muscles are not weak because these muscles are

innervated by branches that arise before the point

at which the radial nerve enters the arcade of

Frohse. In this syndrome, pain and local tenderness

are followed by progressive motor loss. When sensory

loss is present, a more proximal lesion must be

considered.

The electrodiagnostic findings of an

axonal injury to the posterior interosseous nerve

consist of normal radial sensory studies. Normal or

reduced amplitude of the radial motor response

occurs when recording from a distal radial nerve

innervated muscle. Denervation will be found in all

radial nerve innervated muscles excluding the

triceps, brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis

longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, and anconeus

muscles.

For patients with the posterior

interosseous nerve syndrome with significant motor

findings, surgical exploration is indicated. For

patients with a less severe clinical course, rest,

the use of splints, and the administration of

anti-inflammatory medications are indicated.

Wartenberg's Syndrome

Wartenberg's Syndrome

Wartenberg's syndrome is a rare

syndrome that results from the compression of the

superficial radial nerve in the forearm. This

syndrome is characterized by pain in the proximal

forearm and hypoesthesia over the dorsal thumb. No

weakness is present. The compression is usually

caused by trauma or wearing a tight band or watch.

Electrodiagnostic findings of a superficial radial

neuropathy consist solely of a diminished or absent

radial nerve sensory response.

|

Suprascapular Nerve Entrapment

Neuropathy

Suprascapular Nerve Entrapment

Neuropathy

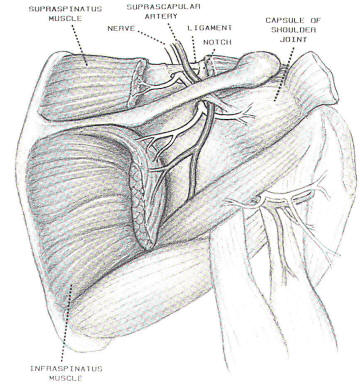

The suprascapular nerve

is a mixed peripheral nerve that

provides motor innervation to the

supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles

(Figure 5). The nerve has no cutaneous

distribution but provides sensory supply

to the posterior capsule of the shoulder

joint. The syndrome of suprascapular

nerve compression includes aching in the

posterior aspect of the shoulder with

weakness and ultimately atrophy of the

muscles involved. Weakness and atrophy

produce difficulty in lifting the arm

overhead and weakness of external

rotation. Wasting of the infraspinatus

muscle is obvious because less tissue

overlies the infraspinatus muscle. The

lack of involvement of the deltoid and

rhomboid muscles differentiates this

lesion from a C5 nerve root lesion.

nerve. The

suprascapular nerve begins as a branch

from the upper trunk of the brachial

plexus and runs parallel and lies deep

to the inferior belly of the omohyoid

muscle. It travels deep to the trapezius

muscle and through the suprascapular

notch into the supraspinous fossa. In

the notch the suprascapular ligament

compresses the |

|

|

Fig-5 |

|

The suprascapular artery

passes superficial to the ligament. In

the supraspinous fossa, the remainder of

the nerve curves around the lateral

margin of the spine to enter the

infraspinous fossa. The suprascapular

notch is a continuum between a widely

patent notch and a bony foramen. The

smaller notch is more likely to be

involved with entrapment neuropathy. The

sling effect in which the nerve is

compressed by the sharp inferior edge of

the ligament. Plain roentgenography of

the scapula, visualizing the notch, may

be helpful in establishing the

diagnosis. Repetitive trauma has been

implicated in the origin of this

neuropathy, although it is observed in

patients with isolated trauma, condition

in a person who used poorly fitted

crutches with excess shoulder depression

and an exaggerated swing.

Conduction studies of the

suprascapular nerve are not accomplished

readily. Denervation in the

supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles,

sparing the cervical paraspinal,

deltoid, and rhomboid muscles. is

consistent with this diagnosis. Surgical

release of the nerve should be performed

early. Relief of pain is prompt, but

that motor function returns slower.

|

|

Thoracic

Outlet Syndrome

Thoracic

Outlet Syndrome

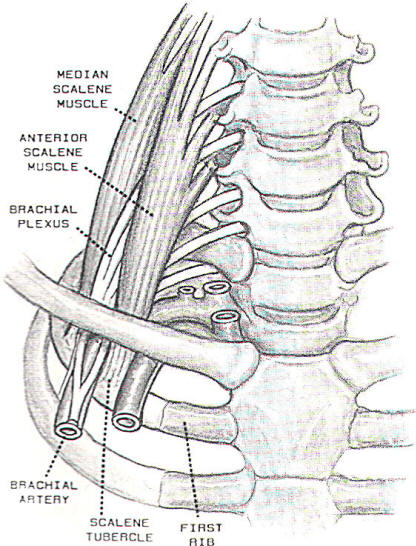

The thoracic outlet

syndrome is a controversial subject. In

some institutions, it is diagnosed and

treated so often that one would think it

constitutes a menace to public health.

In other institutions, it is rarely

diagnosed. Before the controversy is

discussed, the conventionally held views

regarding anatomy, symptoms, findings,

and treatment are described.

The brachial

neurovascular bundle goes through the

thoracic outlet to enter the arm. The

thoracic outlet is divided into the

intrascalene triangle, the

costoclavicular space, and the

subcoracoid tunnel. Most cases of

neurovascular compression occur in the

first portion by an anomalous first rib

or by fibromuscular bands running from

the tip of an incomplete rib or a

prominent C7 transverse process to the

scalene tubercle of the first rib. Other

acquired conditions that can compress

the brachial plexus should be kept in

mind, such as fracture with callus

formation, aneurysms of the subclavian

artery, and tumors (most commonly a

Pancoast tumor).

Wilbourn described five

clinical syndromes. The first is a major

arterial syndrome. This syndrome is

associated with a bony anomaly, such as

a cervical rib. The arterial wall is

damaged and poststenotic dilatation

occurs. Thrombus may be found in the

vessel, disposing to distal emboli and

Reynaud's phenomenon. This condition may

constitute a surgical emergency.

|

|

|

Fig-6 |

|

The second is a minor

arterial syndrome. Eighty percent of

adults reduce or obliterate their radial

pulse when they elevate, abduct, and

externally rotate their arm. Using

photoplethysmography during provocative

tests in normal subjects. Considerable

but asymptomatic arterial obstruction in

60% of subjects and bilateral

obstruction in 33 % of subjects is

noted. The third is the venous

obstruction syndrome. Spontaneous

thrombosis of the subclavian or axillary

vein may be observed in young adults

after vigorous repetitive activity of

the upper extremity. Cyanosis, swelling,

and aching of the limb occur. The

brachial plexus is not involved. The

classification of this syndrome as a

type of a thoracic outlet syndrome may

not be correct.

The fourth is the true

neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. The

major component in this syndrome is

weakness and wasting of the intrinsic

muscles of the hand. This syndrome is

also associated with intermittent aching

in the medial forearm and is the only

widely accepted thoracic outlet

syndrome. The pathologic finding is

usually the fibrous band from a

rudimentary cervical rib to the first

rib that compresses the lower trunk of

the brachial plexus. In 75 % of

patients, all of the intrinsic muscles

are weak and wasted. The thenar muscles

are most severely wasted because the

lower trunk plexopathy most severely

affects median nerve fibers to the

thenar eminence. Rarely will a patient

with true neurogenic thoracic outlet

syndrome have reduced ulnar sensory

amplitude as well as reduced median and

ulnar motor amplitude on the affected

side. Median, ulnar, and radial nerve

innervated muscles, which are also

innervated by the lower trunk and medial

cord of the brachial plexus, will be

denervated. Treatment is surgical

removal of the offending band, The

prognosis for the wasted muscle of the

hand is poor. The last group is termed

by Wilbourn, as the "disputed neurogenic

thoracic outlet syndrome." Most

operations are performed for this group.

Wilbourn, believes that the criteria for

surgery are usually broad and poorly

defined. This pain syndrome is without

anatomic or physiologic changes. No

objective clinical or laboratory

findings exist. Results of

electrodiagnostic studies are normal. No

evidence is present to suggest that

serious neural compression will occur if

the condition is not treated. The

incidence of documented neurosis and

litigation is high in this group of

patients. A moratorium should be placed

on surgery for patients with the

disputed thoracic outlet syndrome; a

significant complication rate associated

with the operation. Postoperative

evaluations by an independent

neurologist reported persistence of

symptoms in the face of the surgeon's

report of excellent results.

In the thoracic outlet

syndrome, as well as in the other

entrapment neuropathies, careful

evaluation of the history and physical

examination and results of

electrodiagnostic studies should permit

proper selection of patients for

treatment and performance of the

appropriate surgical procedures.

|

|